We organised a small cart where we placed a bowl of water so people could wash their hands and try out the soap. Because of the mobility of the cart, we could reach all the separate parts of the old city, from the Christian quarter to the Muslim, from the Armenian to the Jewish. It was interesting to have such a diverse audience and different responses to the work. (Scarlett Hooft Graafland, Interview, May 2010)

It was through this she met Jack and they then discussed the possibility of having a similar installation of the work in Al Ma’mal and Anadiel. The title of the show was ‘Part-time Human’ and it also used soap carved into these same shapes. However, this time the work was used to explore questions in relation to the ‘Jerusalem Syndrome’, a temporary psychological disorder affecting some Jerusalem tourists who begin to believe that they themselves are Jesus.

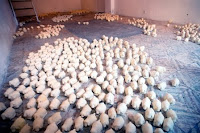

It was through this she met Jack and they then discussed the possibility of having a similar installation of the work in Al Ma’mal and Anadiel. The title of the show was ‘Part-time Human’ and it also used soap carved into these same shapes. However, this time the work was used to explore questions in relation to the ‘Jerusalem Syndrome’, a temporary psychological disorder affecting some Jerusalem tourists who begin to believe that they themselves are Jesus. For the installation at Al-Ma’mal, ‘Part-time Human’, I commissioned the production of hundreds of soap statues from one of the traditional Palestinian soap factories in Nablus. The soap is made out of soda and pure olive oil and is an ancient procedure. It is a famous Palestinian export product in the Arab world and is normally produced in square blocks. The sheep and Jesus statues were displayed on the floor of the gallery with many ‘Jesuses’ leading big flocks of sheep through the space. In this installation, I was trying to ask questions about the ‘real Jesus’, the same questions patients of the ‘Jerusalem Syndrome’ are dealing with (Scarlett Hooft Graafland, Interview, May 2010).

Designing, preparing and creating the components for this installation took a few months and required many trips to Nablus. This was a major undertaking in itself because the journey from Jerusalem passed though several check points necessitating several changes of mini bus. Getting back to Jerusalem with big boxes full of soap was an even greater challenge and not only because of the transport logistics:

When I first started the project, I had no idea it would be so complicated to make it happen. Many times I was stopped at check-points and had to show my belongings and explain why I was travelling with these amounts of soap, and why I was a western woman travelling alone in the West Bank. There was always a general tension with the check-points and the Israeli settlements sitting on the tops of mountains in the West Bank with their rigid architecture that seems to have no connection to their surroundings. It made me realize how hard it must be for people who have to deal with this as a day-to-day reality (Scarlett Hooft Graafland, Interview, May 2010).

When the project was eventually realised, the entire floor of Gallery Anadiel was covered with the soap sculptures distributed in bundles throughout the gallery space. Visitors were compelled to walk around and in between the flocks of sheep led by the 'Jesuses', while immersed in the smell of the soap pervading the space. This gave the exhibition much more than a purely visual impact. Despite the challenges, the success of the project left Graafland with an overwhelmingly positive recollection of the experience:

When the project was eventually realised, the entire floor of Gallery Anadiel was covered with the soap sculptures distributed in bundles throughout the gallery space. Visitors were compelled to walk around and in between the flocks of sheep led by the 'Jesuses', while immersed in the smell of the soap pervading the space. This gave the exhibition much more than a purely visual impact. Despite the challenges, the success of the project left Graafland with an overwhelmingly positive recollection of the experience: The hospitality of the Palestinians I met during my travels in the West Bank and the stunning landscapes of fields of old olive trees, the generosity of the factory owner in Nablus, where sometimes I would stay for days with his family working on the soap production, the interesting and broad art community I met through Al-Ma’mal - I thought it was very special and important to have a Foundation for Contemporary Art in the middle of Jerusalem with such a good program. I experienced a lot of creative energy at the centre and found that Al-Ma’mal was very well known and respected by the Israeli art community too (Scarlett Hooft Graafland, Interview, May 2010).

POSTSCRIPT

Graafland’s exhibition marked the second time that the floor of the gallery had been covered with Nablus soap, the first time being Mona Hatoum’s show at Anadiel in 1996. The soap and the factories had also been beautifully captured in a series of photographs by Issa Freij which were published in Edition 10 of What’s Up? in 1999.

For thousands of years the city of Nablus was exposed to many invasions yet no aggressor had dared to destroy the old city of Nablus and its precious cultural heritage until the coming of the Israelis. It was reported on the 12th of April 2002 that among many other buildings in the old city of Nablus, the Masri, Rantisi and Cana’an soap factories had been destroyed. (Jack Persekian, From 'Nablus Soap', 2010)